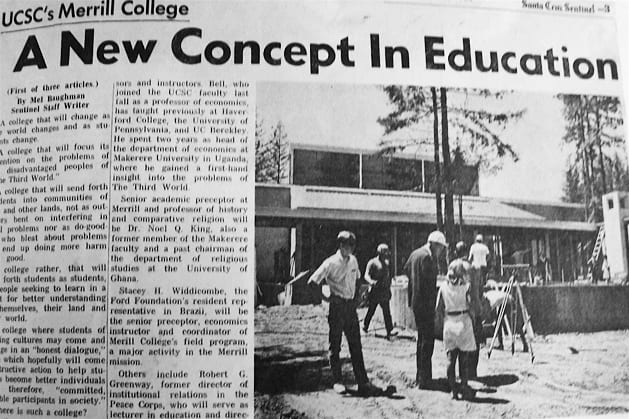

In Fall 1968 I drove across the U.S. in my Volkswagen beetle piled with all my earthly possessions (mostly consisting of books, records and Hi-Fi equipment) to take my position at UCSC. An early gathering of the incoming faculty of Merrill College, which was just then opening its doors had already exposed me to the plans for the college and allowed me to meet my new colleagues. Most of their researches focused on different parts of the world in different disciplines.

I began teaching at the University of California at Santa Cruz in Fall 1968, a most exciting time. In California and the US, the civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam war were at their height. Elsewhere, the newly independent states of Africa, Asia and Latin America (collectively known as the Third World) were struggling to establish themselves in the modern world.

The theme of Merrill College was the Third World, that is, the newly independent states of Asia, Africa and Latin America. Most of the incoming faculty (like me) were completing dissertation on one or another Third World country. There was no existing curriculum for Third World studies at the time. It was up to us to devise one, and fast!

The theme of Merrill College was the Third World, that is, the newly independent states of Asia, Africa and Latin America. Most of the incoming faculty (like me) were completing dissertation on one or another Third World country. There was no existing curriculum for Third World studies at the time. It was up to us to devise one, and fast!

We decided boldly to launch a three-quarter curriculum, to be required of all first year students. The initial topics for each quarter were Africa, the Middle East, Latin America. (Subsequently courses on China and India were added).

Faculty with substantive regional knowledge were tasked with giving the lectures and assembling the reading list for each course. Students were required to attend the lectures and were assigned to required twice a week sections. Seminar discussions would be led by Merrill faculty. Or such was the idea.

Gulf War Reader, 1991

When it was launched in 1964, UCSC was organized around residential colleges, each of which included classrooms, faculty offices and student dormitories. I spent a lot of my time in the early years developing the Merrill College core course, and participating in the development of the History program and UC Academic Senate. It was exhausting, exhilarating work.

Here I want to briefly discuss my involvement in the Merrill core course, of which I was one of the organizers (together with Walter Goldfrank and John Isbister). A key decision was whether to organize in terms of world regions (as mentioned above), or with a general introductory course in the Fall, followed by regionally focused courses in the next two quarters. After much discussion, we opted for a general introduction.

But what would be the purpose of this course, and how would it be organized? What kinds of readings would be assigned? How would student knowledge of the course materials be assessed?

Nothing prepared me for the kind of interdisciplinary collaboration and learning that followed. As a Middle East historian I was trained in the histories of individual states, with a focus primarily on national politics and culture. However at Princeton I did have the good fortune to study with Raymond Grew and Arno Mayer, who were pioneering a comparative approach to European history.

In Merrill I found myself among macro-historical social scientists who operated with comparative historical framework, and the idea of “cases.” Most were Weberians or Marxists, for whom institutional structures and the market were analytically central. Fresh from my fieldwork amongst Moroccan pastoralists I at first found easier connections with anthropologist colleagues. But in the end, I found working with sociologists and political scientists to be more rewarding.

Teaching at Merrill College in the early years was an enormous learning experience. It allowed me to develop confidence in my ability to teach California undergraduates from all quarters.