I left Princeton in 1965 with the tool kit of a conventional European historian of the period: big on political, intellectual and diplomatic history, weaker on social and economic history. In Paris I began working in the French military and diplomatic archives related to early twentieth century Morocco.

Once in Morocco, I began to realize that I lacked an anthropological understanding of Moroccan society. I spent the summer of 1966 in Morocco and was introduced to anthropologist David M. Hart. He liked nothing better than introducing younger scholars to anthropology. With his help I began a crash course in social anthropology. Through him I was able to meet Ernest Gellner at the London School of Economics, and E. E. Evans-Pritchard in Oxford. Subsequently in Rabat, Morocco I met anthropologists Clifford and Hildred Geertz and their graduate students, Lawrence Rosen, Dale Eickelman and Paul Rabinow.

In December 1966 I returned to Paris, where I met Ross E. Dunn, a Ph.D. candidate in History at the University of Wisconsin. He was also working on pre-colonial resistance to the French protectorate in Morocco. Unlike me, Ross had been trained as an historian of nineteenth and twentieth century Africa, well versed in tribal societies and rural sufi orders. Ross’s research focused upon the tribes of south-eastern Morocco, whereas by this time my focus was central Morocco. We quickly became friends and collaborators.

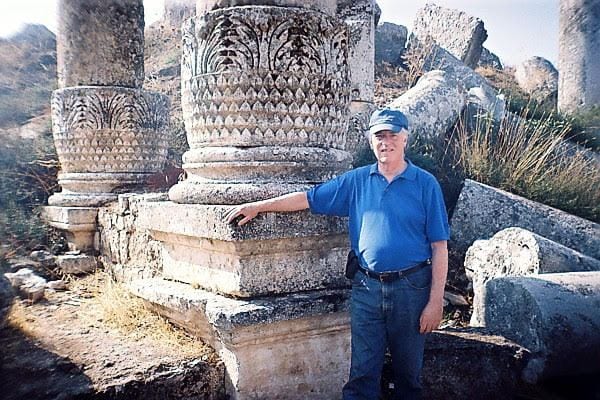

Anthropologist Lawrence Rosen became a life-long friend and collaborator. In August 1967 we collected oral histories among elderly Morocco men who had fought against the French in the pre-colonial period. It was exciting to meet the actual individuals who were named in French military records of the period that I had viewed in Paris.

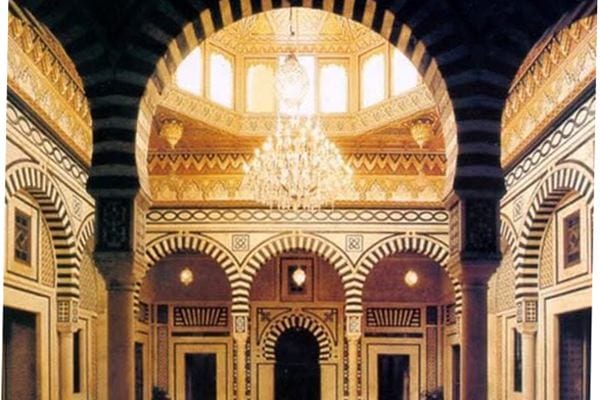

Fanatasiyya

Two other graduate researchers of the period played an important role in my initiation to matters Moroccan. They were political scientist John Waterbury, who was then preparing a dissertation on the party system of post-independence Morocco using anthropological research, and historian Kenneth Brown, a UCLA Near East Studies graduate student who dissertation was on the social history of Salé, a small Moroccan coastal town adjacent to Rabat.

As a result of my two year’s interaction with these new friends I returned to the US a well-trained researcher on Morocco (with passable Arabic). Without these encounters, and the intellectual sparks they set off, I would never have been able to complete my dissertation on pre-colonial Morocco.

My work on Morocco was germinative of my interest in social movements and of Orientalism and Empire.

I continued to write about Moroccan history over the course of my career, culminating in the production of The Ethnographic State: France and the invention of Moroccan Islam (California, 2014).